Jan 31, 2021 —

Everything is bigger in Texas. Even the blackouts. And also the question it raised: Does wind power threaten America’s future. Fortunately, that huge question has an easy answer — No. Here’s why. There are plenty of wind turbines in places like Iowa and Minnesota that are outfitted with heaters for cold weather, and they work just fine.

After the 2011 debacle that froze Texas gas and froze people out of their homes as far away as Taos, New Mexico, Texas regulators suggested weatherization. But the “freewheeling Texas electricity market,” as the Wall St. Journal called it, didn’t require it. Decent regulation could have fixed the wind problem, which was quite small because wind is still not a big player.

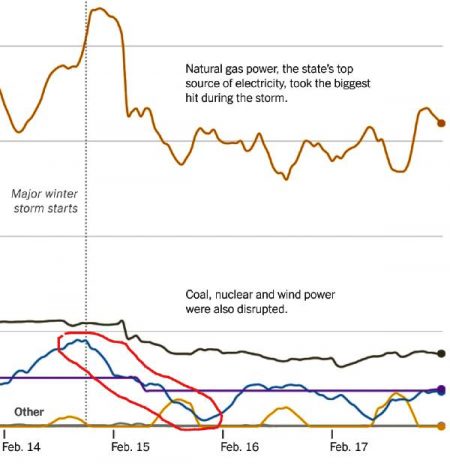

Well, that’s the story so far. But there’s a fly in the ointment that has not been reported. Look at this graph.

The blue graph is wind-power output. Notice that in the section that I’ve circled in red, wind power drops off as soon as the “Major winter storm starts.” And it drops for about 27 hours to almost zero. It drops by at least 90%. And right in the middle of this is when the blackouts start.

The big problem (and it was at least twice as big and much more sudden) is the drop-off from gas-powered generation. So, no, wind was not at all the main problem. But if we are going to rely mostly on wind power, we wouldn’t want it dropping by 90% at exactly the wrong time.

So why did wind power drop so low? Three possible reasons. (1) The wind stopped blowing (no, quite the opposite, this storm had huge winds). (2) the turbine blades iced up (but we are told only about 30% did). (3) The wind started blowing too hard. Yes, that’s possible. When the wind blows too hard wind turbines shut down automatically to avoid damage. Apparently, this last possibility is what accounts for most of that 90% drop. This indicates we are going to need fossil/nuclear backup generation that can cover most of the power needs right when they are greatest.

This needs more looking into before people jump to conclusions. It doesn’t mean we couldn’t get most of our power from wind, but it may mean we need a lot more costly backup generation than people have assumed.

And it could mean that wind is not the cheapest answer to the climate problem. That’s my guess.

Question #2: Are the Texas Regulators to Blame?

In January 2004, New England experienced a very similar blackout with freezing weather shutting down gas and some coal plants. So the electric regulator decided to use a “capacity market” to buy more generating capacity and improve its reliability. I was called in as their expert economic witness to win approval for it from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. We won approval, then the New England politicians objected, so Peter Cramton and I designed them a new market.

Cramton was elected vice-chairman of ERCOT, the Texas regulator, the day before the storm hit. But the Texas market is different than the one we designed for ISO New England. Texas uses an “energy-only market.”

There are two different approaches to the reliability problem:

- Regulate electricity prices (“energy only”).

- Regulate the quantity and quality of generating capacity.

The first approach hopes that investors will build enough high-quality generation when they see the high regulated prices that they can earn by providing emergency power. That’s the indirect approach, and in my view, it’s more likely to fail to take care of problems that are infrequent and hard to predict — like, say, freakish winter storms that only happen every thirty years.

So why does Texas trust approach #1? This is how I see it. But first let me say that Bill Hogan, the mastermind of the regulated “scarcity prices” used in Texas, is a very smart, well-meaning Harvard Prof. who is doing his best to make electricity reliable at the lowest possible cost. But, he’s not trained as an economist. So his story is this:

- “Scarcity prices” are an economic concept and they are optimal. [not]

- Market prices are optimal, so Hogan’s prices are market prices. [not]

- So even though the regulator sets prices, this is a market approach.

(Even the Wall St. Journal buys this: “The result was a laissez-faire market design.” No, it’s not.) - Market prices are best.

A lot of times they are. But sometimes, when it really matters, they aren’t.

If ERCOT would like to check this out, I suggest they get themselves a pile of econ textbooks and look up “scarcity price.” They won’t find it. Hogan made up the formula. Some say it’s a good approximation. The problem is, there is no coherent concept being approximated. It’s all a charade.

Of course, the Texas prices aren’t crazy. They need to be high to attract backup-generation that is almost never needed. But they are not market prices and even if they were, prices are not very good at controlling investments that are ultra-long-shot gambles. But the pretense of economic theory and ideal markets obscures this common-sense reality.